I took up Coach Carole’s Thursday GenAI Club challenge for Week 2: Time Travel Thursdays. The prompt invited us to time-travel with a favorite ancestor, so I adapted it for my husband’s great-grandmother, Catherine—who just happens to be the subject of my next novel (Countess of Cons: The Story of a Gilded Age Grifter).

I asked for a scene about a 50-year-old divorced woman selling (sometimes illegally) diamonds in 1890s Chicago. The first draft was fun, but Scripty (my AI pal) suggested grounding it in Catherine’s real haunts—Palmer House, Marshall Field’s, the Auditorium Hotel—and the result was too good not to share.

This scene is pure imagination, not history, so it won’t appear in the finished book. But I thought you might enjoy this little taste of Catherine.

Catherine opened her eyes. It took her a moment to remember where she was—a rented room at the Palmer House Hotel, the grandest address in Chicago’s Loop. The gaslight burned weak and wavering, the damask curtains heavy with dust and smoke. She sat upright, taking care not to jolt her pounding head. She slid her legs to the side of the bed, letting them hang until she felt they would hold her upright.

Once steady, Catherine moved through the steps to ready herself for another day. She smoothed her skirts, twisted the diamond ring on her left hand until the skin blanched, and tucked a muslin-wrapped pouch into the lining of her valise. At fifty, she cannot afford hesitation; every morning begins with resolve.

By midmorning, the city was already roaring. She stepped into the bustle of State Street, dodging the electric streetcars that clang past and the factory girls rushing toward Marshall Field’s. She drew a deep breath, catching the smell of coal smoke, roasted chestnuts, and fried onions from the street vendors. Chicago hummed with commerce and spectacle—perfect cover for a woman selling diamonds that may or may not be what she claims.

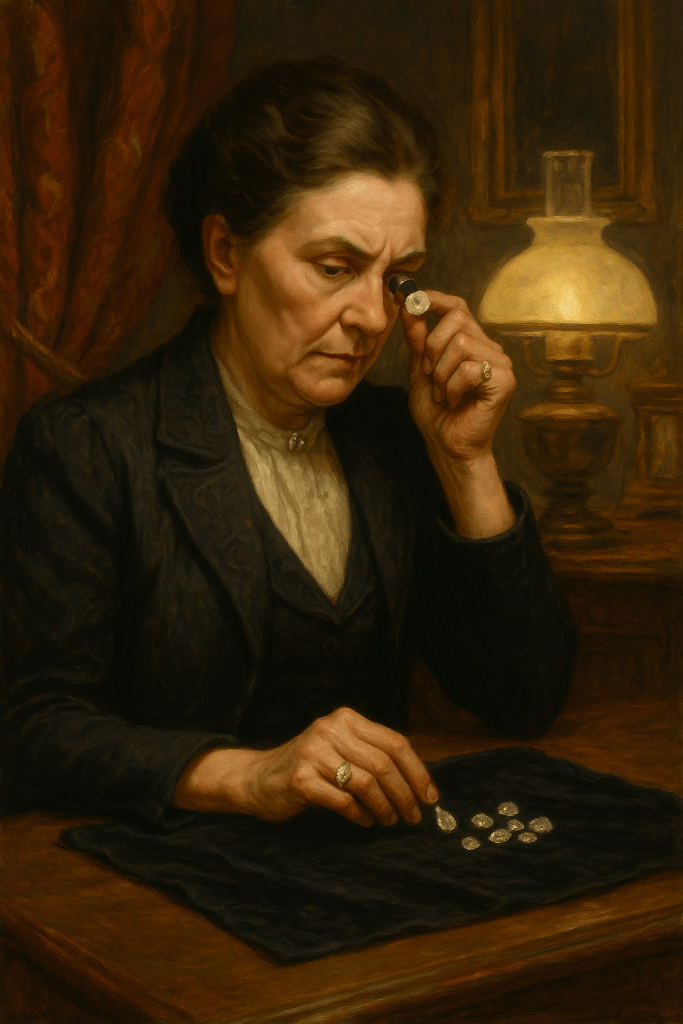

She glanced at her modest tools: a velvet square, a jeweler’s loupe, and a practiced story. “Estate pieces,” she told one buyer. “A widow’s lot,” she confided to another. Sometimes the stones were genuine, sometimes questionable, and occasionally paste glass with a convincing sparkle. Her success depended on balance: too eager and she seemed desperate, too hesitant and the buyer grew suspicious.

Her stomach growled as midday approached. She entered Huyler’s, settled on a stool at the counter and ordered a coffee. As she sipped, her thoughts drifted back to her first attempt just months earlier. The Auditorium Hotel rotunda had been full of businessmen and traveling salesmen reading their papers. She had only one stone then—a small diamond her cousin insisted would fetch a decent price. Her hands had trembled as she laid it on a scrap of velvet, murmuring about debts and a need for discretion.

The buyer, a jeweler’s clerk from Wabash Avenue, examined it with a loupe, nodded slowly, and pressed a roll of bills into her hand. For the first time since her divorce, she felt a jolt of power. The transaction had not been just a sale; it was survival, wrapped in secrecy and nerve. That night, as she lay awake in her rented room, the money hidden beneath her pillow, she understood: diamonds could buy her freedom, if she had the courage to keep selling them.

Now, in 1892, the routine was well established. Jewelers on Wabash Avenue and State Street knew her—by one name or another. In the Marshall Field’s rotunda, she lingered, observing which clerks look green enough to be persuaded. Sometimes she tried her luck at the Auditorium, sipping sherry and striking up conversation until the moment feels right to suggest a private appraisal.

Each encounter was a performance: the glide of her hand as she opened the pouch, the quiet authority in her voice as she explained a stone’s supposed origin. Behind the mask is calculation and constant vigilance—who might betray her, who might call the police, who might be fooled.

By evening, her feet ached from the cobblestones, her corset pinched, and her nerves were frayed from the day’s bargaining. She sank into the red cushioned chair in the Palmer House dining room, pushing beefsteak and potatoes around the plate, occasionally taking a small bite as she surveyed the room for a possible new mark

Back in her room, she counted the day’s take—crumpled bills, the occasional promissory note—measuring not only profit but also risk.

When she finally extinguished the gas lamp, the pouch of stones lay beneath her pillow. Outside, Chicago’s Loop thundered on: carriage wheels, saloon laughter, a piano drifting through an open tavern window. She closed her eyes, knowing that tomorrow she would once again sell illusions—diamonds that glittered as much with her nerve as with their cut.

Did you enjoy this glimpse into Catherine’s life? Be sure to subscribe in order to receive future posts.

Leave a reply to paulalimput Cancel reply